The geoglyphs at Monte Sierpe are amongst Peru's most enigmatic and unexplainable mysteries

The Avenida de los Hoyos, a geoglyph like the Nazca lines consisting of a series of large basin-like potholes along a mountain ridge, appears to slither up the slope for miles.

Very little published information can be found about the strange holes aside from a few notes written about them by Erich von Daniken (in his novel Evidence of the Gods in which he attempts to tie such enigmas into his theory of alien visitation) and footnotes in the works of Federico Kaufman Doig (Peru's famous archaeologist who coined the name 'Avenida de los Hoyos'). Lucio suggests the only source of knowledge is cultural: “We don't know much about pre-inca history because it is not recorded in written language but rather with icons in various forms”.

Our quest for answers to the mystery of Avenida de los Hoyos begins with an expedition to the site. We set out from Paracas, passing Pisco, then another thirty minutes drive past Humay to Tambo Colorado where, Lucio explains, there is another archaelogical site that may help us uncover the meaning and intent of the strange geoglyphs nearby at Monte Sierpe. The drive following the Pisco River is beautiful - a green valley with a contrasting desert mountain backdrop.

At Tambo Colorado we discover a vast site with many crude tombs. “Tambo Colorado has been dated during the Inca period however it is important to remember that while the Incas were conquerers, they did not always conquer other cultures by force” explains Lucio.

Rather, the Incas forged a powerful relationship with the Chincas who were the dominating culture of the area in the time. “They built structures in harmony with older sacred sites to forge their relationship with the inhabitants and we see that here in Tambo Colorado, structures in the style of Inca beside much older structures and crude tombs built prior to and not in the finer Inca style” concludes Lucio. While artifacts and burials from the Inca period have been found in the tombs themselves, Lucio feels that the tombs are likely pre-inca and likely thousands of years old.

Backtracking our route from Tambo Colorado, just a few minutes away, we arrive at the ghostly remains of Monte Sierpe — a once-vibrant town now eerily silent. The town was rocked by a powerful earthquake in 2007, reducing nearly all its structures to rubble. “The town was destroyed by the earthquake, not a single building was left standing,” explains Lucio as he points toward what’s left of the town’s church — a cracked bell tower stubbornly standing amid collapsed walls, defying time and tragedy.

Walking through the debris-laden streets, a somber atmosphere surrounds us. It’s hard not to feel a deep sense of loss — not only of architecture but of community, culture, and memory. Nature has slowly begun to reclaim parts of the village, with plants creeping through cracks and wind whistling through broken windows. Yet, despite the destruction, Monte Sierpe retains a strange kind of beauty, as if frozen in time to remind us of both resilience and fragility.

Lucio points out that Monte Sierpe was once a key settlement near the Pisco River, inhabited by people with strong ties to the surrounding landscape. The earthquake not only reshaped the physical space but also transformed the way the locals relate to it. “It’s a sacred place now,” he says. “A site of memory and reflection.”

Our hike begins along irrigation canals then within a few hundred meters we arrive at the foot the Picaduras de Viruela. “This name [Picaduras de Viruela] is terrible - it was adapted by the locals in the 1930's when the holes were discovered by plane and those who discovered it offered the name only by virtue of the glyph's physical aspects and nothing of it's history. We hope to discover it's true name or offer another with respect to the original creators' intent. Otherwise we can settle with Avenida de los Hoyos”.

We find two large rock-lined excavations, similar to those at Tambo Colorado, at the base of the geoglyph. They are still littered with human remains, skulls and bones mostly. The 'tombs' are crudely constructed similar to those we have seen in Tambo Colorado and we are inclined to accept Lucio's conclusion that they are likely pre-Inca as the style of construction resembles nothing of the fine stonework during the Inca period.

One of our crew remarks how odd it is that these bones still lie here strewn about without being catalogued and open for anyone to loot. Lucio helps us understand the urgency of revealing the wonder at Monte Sierpe's true nature: "Peru is full of ancient burial and ritual sites - especially near the coast where the climate is particularly dry and preserves them”.

“With thousands and thousands of such ritual sites, our government is forced to choose which can be preserved and which cannot. This is why it is vital that we reveal this enigma's true significance. You can still find artifacts like pottery and other unusual items, but already so much archaeological information has been looted. Please, let us leave what remains in its place,” pleads Lucio, his voice echoing over the dry wind as we descend into one of the enigmatic troughs.

Respectfully, we heed his plea. The temptation is real — we come across fragments of ancient pottery, obsidian chips, and even more striking: the tiny jawbone of a child, followed by what appears to be part of an adult female skull. These discoveries are haunting, yet they emphasize the sacredness of the site and the responsibility we hold.

We continue along a narrow ridge between two valleys, our eyes scanning the geometric patterns of the holes below us. Every few meters we stop, crouch, and observe. The formations are hypnotic — perfect circles stretching into the horizon like an ancient code etched into the Earth. The holes are approximately one meter in diameter and reach a depth of around 80 centimeters. What is most surprising is their construction: each one lined with stones carefully arranged, as if to preserve their shape for eternity.

The silence is almost ceremonial, interrupted only by the crunch of gravel under our boots. One cannot help but wonder: were these graves, storage pits, astronomical markers, or ritual sites? Lucio believes they may have served multiple purposes across generations, their meaning evolving with time.

As we move forward, the scale of the site becomes apparent. There are hundreds, possibly thousands, of these openings across the landscape. “This is not a random occurrence,” Lucio whispers. “Someone wanted to be remembered.”

The walk up the ridge is strenuous and testament to the monumental human effort that went into excavating and rock-lining well over five thousand holes that meander up this mountain ridge - tough rocky terrain. We are relieved to reach the plateau before the summit and take a few minutes to hydrate and reflect on the human toil that must have been required to complete such an undertaking.

But before we've had time to atrophy in contemplation, Lucio instructs us to observe the biology of what otherwise seems to be a completely desolate terrain. He shows us a lichen colony thriving on the rocks isolated to this nearby area. Finally the strangest flower blooming, seemingly out of nowhere, at the finality of the holes before the summit. Having past two kilometers of sheer dry desert terrain it is hard to comprehend how this flower blooms where it is.

From the flower's vantage is where we can distinguish the serpents head carved from the summit which had not been clear from our vantage point on the ridge plateau. “Many people miss the head of the serpent - it only becomes clear from a certain point and certain time of day when the shadows give it dimension” explains Lucio.

But even from the height of the ridge plateau we can not make out the entirety of the serpent's body as it meanders over ridge and hill and along valleys. For that, Lucio informs us, we must hike the summit. Although the incline changes dramatically, the rocks seem to make easy steps and we hit the top thirsty but in great spirits.

The view is absolutely spectacular. From this elevated vantage point, surrounded by jagged mountain peaks and soft golden hills, we gaze down upon the valley below. Serpentine patterns stretch across the earth, winding with purpose and precision — a monumental geoglyph whose magnitude only becomes clear from above.

Silence falls over our group. It is a moment of repose, of shared reverence. We find ourselves standing exactly where the ancients must have once stood, staring at their creation, marveling at its power and scale. The sun casts long shadows across the terrain, accentuating the curves of the formation. For a moment, it almost seems to move — to slither, alive, through the landscape.

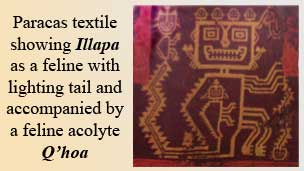

Lucio breaks the silence with a solemn tone. “I believe that what appears to be a serpent is actually the ancient deity Q’hoa,” he says, pointing along the undulating body of the geoglyph. “He was the servant or acolyte of the god of water, known as Illapa. His likeness was used in many rituals to call upon the rains.”

Suddenly, everything begins to make sense. The scale, the direction, the effort — it was not just a marker or a signal. It was a prayer carved into the earth. A tribute to the forces that governed life in the desert. A plea for survival, written in a language of stone.

We begin to see with new eyes. The Avenida de los Hoyos is no longer a mystery of holes — it is the body of a god, winding its way between mountains and centuries, still watching over the land it once nourished.

Historically, we know that many civilizations in Peru thrived and perished based on the changing climate on the periphery of the Atacama desert. Many deserts, especially the Atacama, are able to lock in their mineral wealth due to extreme aridity and with rain become highly fertile for farming. And while our modern climate science has unraveled the workings of smaller climate cycles such as the El Niño oscillation, the longer climate cycles are beyond our history of climate record-keeping. It appears that areas in Peru may have been fertile for hundreds of years, then suffered drought for hundreds of years after.

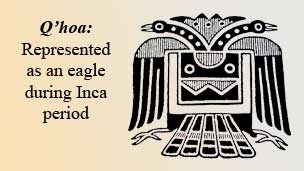

Lucio continues describing Q'hoa: “He took many forms but he is consistently depicted with a body comprising of concentric circles that represent water or water-drops. His urination were the rains that brought life-giving water to the farmers. While his face is often that of a feline, his body was made long and serpent-like, sometimes a tribute to rainbows, other times a tribute to rivers that engorged after the rains he brought. In some depictions he had wings and legs and much later on he took the form of an eagle”.

Cultures of several ages worshipped Q'hoa and rituals in his favor were made often in pleas for the rains to come and end droughts. “Civilizations may come to an end but people and cultures simply do not just disappear". As Lucio contends, throughout many periods in Peru, a culture we know little about today, known as the Chavín, assimilated other cultures through religion.

Lucio explains their ability to assimilate with a smile: “their success in assimilating neighboring cultures was their powerful religious figures and San Pedro". San Pedro is a hallucinegic cactus that, no doubt, the Chavín used to convince their neighboring cultures in the existence of their deities. The Chavín introduced and popularized the gods Q'hoa and Illapa and rituals in their name to their neighbors.

This early culture not only brought gods and rituals to new areas, they brought their technology as experts of the day in controlling water. They built canals around their temples and buildings to protect them from the regular El Niño floods which are known to be very powerful in Peru. But for reasons that remain unclear, the influence of the Chavín declined as new civilizations sprang forth.

“Human survival and success demands that we seek greener pastures. Even today we see peoples in depressed areas migrating to lands where there is greater prosperity and the chance of greater success". Lucio's analogy explains the apparent disintegration of the Chavín culture as the Paracas culture came into being.

“While they started out as humble fishermen, the Paracenses later on became great farmers during a period when their lands were fertile and humid. They would dig great canals in locations where the water table was high, just deep enough so that the roots of plants could reach water. During their reign they discovered cotton and textiles and forged trading routes with the highland peoples near them who were also learning to domesticate Vicuña whose fur could also be used in textile making”.

.jpg)

As the Chavín culture gave way to the Paracas culture, so too did Paracas give way to Nazca culture which perfected irrigation and water management for farming. They built great aqueducts that moved water in vast quantities from the river valley to the surrounding plains (probably in response to drought) and they perfected textile craftsmanship and pottery-making. But this great civilization was destined for a great suffering - a climate shift appears to have run the rivers dry.

“Nanazca is a word in Quechua which means pain or suffering. It seems certain this period, the area, and the civilization itself [Nazca] was later named after this great decline”. Lucio's insights into cultural history help us understand their urgency for water and their inclination to appeal to their gods for help. Estimates of the building of the Nazca aqueducts occur during the third or fourth phase of their culture. It seems likely their construction were in response to a great drought.

“I believe that the geoglyph at Monte Sierpe was created during the drought that ended the Nazca civilization - clearly there is the motive. And if we study the shape of the figure we can see strong commonalities with other representations of Q'hoa - the concentric circles representing water or rain, the long body terminating in a head with mouth agape”. Lucio's explanation has convinced us and although the details of the serpent's head are far to weathered to make out the signature feline head found in other representations, the long body and concentric circles are Q'hoa's trademark.

But significance of the geoglyph at Monte Sierpe, as Lucio explains, does not end there: “This geoglyph may be proof that the Nazca civilization believed it could speak and appeal to the heavens using great marks on the earth”. Like castaways on a deserted island forming 'S.0.S.' on the beach to signal passing planes, it is feasible to think that these early cultures might have believed it possible to communicate with the heavens and clouds (their gods) through geoglyphs. And if this notion is acceptable, then the geoglyphs at Nazca may have been part of the same appeal.

“While the Nazca lines and other various geoglyphs in the surrounding region do not necessarily represent Q'hoa, they do certainly represent animals, humans, and life - what might be appeals to the gods to bring rain to bring life to the land. If we consider Kaufman Doig, then the Nazca monkey is also a representation of Q'hoa”.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

📍 Where is Monte Sierpe located?

Monte Sierpe lies near the town of Humay, in Peru’s Pisco Valley. It is accessible via private tours or guided excursions from Paracas.

🕳️ How many holes exist on site?

There are over 6,000 meticulously arranged holes stretching across nearly 1.5 kilometers of desert ridge — a feat of ancient engineering.

🧭 How can I get there?

Most visitors depart from Paracas or Pisco by private transport toward Humay. From there, it requires a short hike. Several agencies offer guided, culturally enriched tours.

⚠️ Is the site protected?

While not formally designated by UNESCO, Monte Sierpe is the subject of ongoing preservation efforts by local researchers and cultural organizations.

🔍 What’s the purpose of the holes?

Their origin remains a mystery. Hypotheses range from burial grounds and food storage to spiritual altars or even astronomical calendars aligned with Andean cosmology.

⛏️ Is excavation allowed?

Only authorized academic teams may conduct research. Visitors are urged to respect the site and avoid removing or disturbing any elements.

🌌 Can I see the full serpent shape?

Yes — but only from above or from select ridgeline vantage points. Local guides help interpret its serpentine form, believed by some to represent the deity Q’hoa.

📸 Is photography allowed?

Photography is welcome, as long as it is done respectfully. Drone use may require permits from SERNANP or the local municipality.